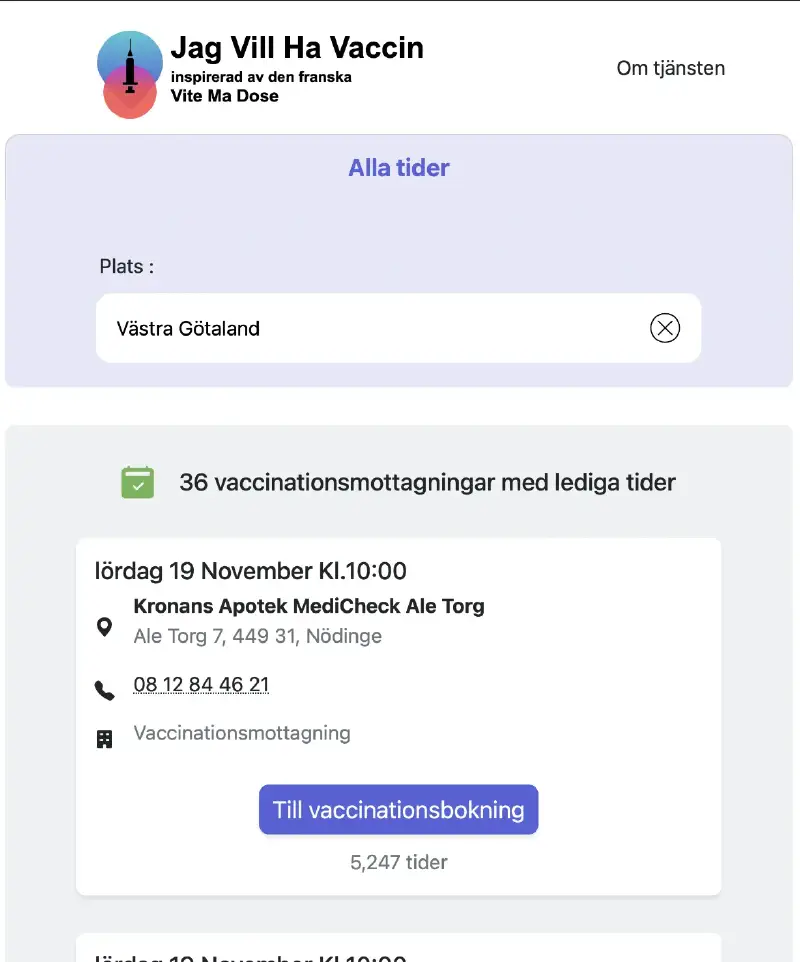

jagvillhavaccin.nu Source code (scraper) Source code (frontend)

Finding a vaccine time in Sweden#

Like other countries, Sweden began vaccinating its population in early 2021, starting with the most vulnerable and gradually expanding the campaign to younger age groups. However, Sweden’s healthcare system is regional and decentralised, with surprisingly little collaboration between regions. In particular, the digital systems used in Swedish healthcare are often criticised for their lack of common data standards and APIs, and a tendency to either reinvent the wheel (at great expense) or fall into the hands of ineffective monopolies1.

This was a poor foundation for a vaccination campaign where everyone expected to book appointments online. The result was exceptionally… varied, though I could not have anticipated quite how chaotic it would become when I first started this project.

A few regions used 1177, a robust service in terms of authentication and interface, but one that completely lacked a way to get an overview of available times and locations. The regions of Stockholm and Gotland chose their Alltid Öppet app, a proven solution for other healthcare bookings. Unfortunately, the app did not allow users to see available slots without logging in via BankID. This led to numerous crashes when hundreds of thousands of people tried to access the few hundred slots added periodically, which in turn hindered patients trying to access more critical care2. It was also reported that the Region of Stockholm had to invest several million crowns in server capacity just to meet this largely unsuccessful demand. One region simply abandoned online bookings entirely, choosing to contact all citizens individually by phone. Finally, the remaining regions opted for private solutions with surprisingly poor user experience. In Södermanland, users had to manually click on every vaccination centre to check for availability in the current week, then click through several times to explore subsequent weeks. The worst experience was for citizens in Västra Götaland3 and Skåne4 5, where authorities delegated the booking infrastructure to each individual centre. Min Doktor, Din Doktor, Doktor.se… In cities like Gothenburg and Malmö, it was not uncommon to have to create 3–4 different accounts just to see the (un)available slots in the centres within a single district.

In comparison, across the Öresund, the Danish government had established a single portal. Right next to the login button, a clear sign deterred users from logging in if no appointments were available.

The French example#

France was initially even more chaotic; much like the worst Swedish examples, the government had delegated booking responsibility to each vaccination centre. These centres used 5–6 different e-healthcare platforms. While they showed available slots without requiring a login, it was still far from easy to navigate.

France has a strong culture of “hacktivism”, individuals who create software and use their skills for the common good. Many solutions emerged during the pandemic, but one gained incredible traction: Vite Ma Dose. Started by Guillaume Rozier, the platform aimed to gather vaccine bookings into a single, simple interface for the entire country. The code was open-source, and the website scraped available slots from hundreds of vaccination centres every minute.

Quickly, over 100 people joined the project, maintaining data flows and improving the website’s search functions and accessibility. Within days, mobile apps were available on app stores6, and communication materials were created to reach all audiences. Traffic exploded. Recognising the benefits of this grass-roots solution, the French government quickly decided to support and promote the initiative. Vaccine platform providers also established APIs to make it easier for their data to be republished, seeing the new site as a welcome buffer that relieved their own servers from the millions of visits they had experienced early in the campaign. By the end of the year, over 100 million visitors had used the website.

Guillaume Rozier was eventually awarded the National Order of Merit, with the government praising his and others’ initiatives for saving lives and helping millions of people7.

Creating “Jag vill ha vaccin!”#

Like most French people, I heard of this initiative when the media began covering it in early April 2021. The source code was straightforward, and I decided to spend a few hours investigating whether it would be possible to reproduce the same service in Sweden. I looked into how vaccine bookings were made available across all regions and quickly realised that many could be scraped automatically. None provided open data, but a script simulating user behaviour could save the information in a structured format. I spent a full weekend setting up a prototype. By the end, I had a version based on the original Vite Ma Dose code, initially still in French, but displaying Swedish vaccination centres. I quickly translated the page and published it under the name “Jag vill ha vaccin!” (I want a vaccine!) with a short post on LinkedIn and Twitter. It took off almost immediately.

The reception#

Despite my limited reach on these platforms, the posts went viral, and over 10,000 people visited the website on the first day. Volunteers reached out to help with proofreading and data analysis, and several journalists contacted me8 9 10. I was taken aback, especially as their questions often framed my modest prototype as a solution to the failures of the regions and their massive budgets. At the time, I knew little about just how flawed some of their systems were; I had mostly started the project as a fun experiment.

What I also hadn’t foreseen was that these same journalists would ask the regions why a single individual could deliver what they could not. Press secretaries, often without understanding the service, advised against using it11, citing potential data theft and security risks. Some platform providers even modified their systems to make it harder for me to retrieve data. Since none of the regions reached out to me, I took the initiative to contact them myself.

I contacted every region and managed to secure meetings with about half of them12. Most were adamant that I should stop. Their reasoning was often confused and driven by fear, though one valid argument was that users might miss mandatory information by skipping the official landing pages. I addressed this by ensuring all users were redirected to the official information pages on the respective regional websites. Another concern was the hypothetical risk of the service distributing viruses. Jag vill ha vaccin! did not track users or collect any personal information, but regardless of who I spoke to, the regional employees’ technical understanding was limited. I suggested they reuse the source code and host it themselves, but the culture of open source is unfortunately weak in the Swedish public sector, and no region accepted the offer13.

I vividly remember a meeting with Daniel Forsberg, then a leading politician on the matter for Region Stockholm (now a lobbyist). I offered to display their vaccination slots on Jag vill ha vaccin! to relieve the heavy traffic on their app. He repeatedly stated how “pro-innovation” he was and how much the region valued open data, but explained that in this specific case, it was unfortunately not welcome12.

In the end, only one region welcomed the collaboration: Västra Götaland. Regional executives had recognised the disastrous situation they were in, where over 15 private providers were releasing slots on proprietary platforms, making it harder for citizens to book and for them to get a clear overview of dose distribution. A small team, including Marcus Österberg (creator of webperf.se), was tasked with building an official aggregation page. A strong advocate for internet standards and openness, Marcus quickly published the region’s data openly14.

This allowed me to make the service more comprehensive. Ironically, Jag vill ha vaccin! still displayed more slots than the region’s official platform, as their team had to ask for data from private providers15. I simply scraped it without seeking permission, knowing that the Freedom of Information Act and the public interest were on my side.

The end#

Unfortunately, the project never received the institutional backing I had hoped for. Despite popular support and media coverage, I could only aggregate about half of the country’s vaccination slots, and several regions insisted I shut the service down. I was even personally threatened with lawsuits by the manager of one healthcare centre.

Although I never shut down the website16 17 18, the number of visitors gradually decreased after the initial peak. Jag vill ha vaccin! eventually became irrelevant once the majority of the population had received their first dose and scarcity was no longer an issue.

Whenever journalists reached out, they were often seeking critical quotes to build an antagonistic narrative. I explained that the entire history of vaccination slots gathered by the site was available as open data and could be used to analyse the effectiveness of the rollout. I used it myself to report on centres with hundreds of available slots while other parts of the same region had none. Unfortunately, this kind of analysis required more time than most journalists were willing to invest, so the data remains mostly unused to this date (if you are a researcher, feel free to message me—I have archived it 😉).

Moral of the story#

Unlike its French counterpart, and to my initial disappointment, Jag vill ha vaccin! never became a government-backed success story. However, success was never the primary goal, and this project taught me a great deal. Not only technically but also about the challenges of innovating in the Swedish public sector.

References#

Detta gick snett med Millennium i VGR (lakartidningen.se) ↩︎

Svårt boka vaccintid när spärren lyftes: ”Det fungerar inte” (molndalsposten.se) ↩︎

Vaccinstrulet tvingar regionen annonsera för att fylla tiderna (sydsvenskan.se) ↩︎

Vite Ma Dose tops the App Store rankings (in French, leparisien.fr) ↩︎

Guillaume Rozier receives the medal of national merit (in French, 20minutes.fr) ↩︎

Nystartad privatsajt visar tusentals svenska vaccintider (svd.se) ↩︎

Pierre skapade sajten som är lösningen på vaccin-kaoset (emanuelkarlsten.se) ↩︎

Regionens uppmaning: Använd inte nya bokningssidan (svt.se) ↩︎

Presentations from my meetings with the regions are available here ↩︎ ↩︎

Regionen inte så intresserade av nya sajten för att boka vaccin: ”Vår egen fungerar ganska bra” (smp.se) ↩︎

Hjälp VGR testa vårt API med öppna vaccintider (vgrblogg.se) ↩︎

Sidan skulle samla lediga tider - ännu saknas manga (archived) ↩︎

Egenutvecklad vaccinationssajt igång igen: Listar många lediga tider (nyteknik.se) ↩︎

Regionerna motarbetade sajten som ville effektivisera vaccinbokning – nu är den tillbaka dubbelt så stor (emanuelkarlsten.se) ↩︎

‘It’s a democratic tool’: The site that helps you find a Covid vaccine slot in Sweden (thelocal.se) ↩︎